The Irish linen industry once employed over 40 percent of Northern Ireland’s working population, but sadly most of the mills have since closed down. I took a tour of Northern Ireland to visit some of the manufacturers still remaining in this often forgotten part of the UK textile industry. Read on to find out what I discovered.

Whilst I have been writing about and visiting UK manufacturers for nearly a decade now, I am ashamed to say that I have never ventured over the water to Northern Ireland, once synonymous with the words Irish linen.

Whilst I have been writing about and visiting UK manufacturers for nearly a decade now, I am ashamed to say that I have never ventured over the water to Northern Ireland, once synonymous with the words Irish linen.

So when I got a call from Invest Northern Ireland inviting me to speak at a textile event they were holding, I couldn’t say no. And I’m so glad I didn’t!

Richard Pelan, Innovation Advisor for Invest NI, kindly took me to visit some of the manufacturing contacts that he’s been working with. Over two days I visited 6 of the best textile manufacturers that the UK has to offer.

What amazed me was how diverse the products that they made were, but what they all had in common was they were innovative and growing companies.

Read on to find out who I visited and the products that they make, but first, a little bit about the history of textile in Northern Ireland…

Back in the day the Irish textile industry was huge, employing 70,000 people at its peak over 37,000 looms. Everything centred around linen and practically every town and village had a mill or a factory. In 1955 there were 55 linen spinners in Northern Ireland, but sadly there are no more. The last closed in 2009. And the last weaver of any substantial size is Fergusons, which you’ll read about later.

Whilst many people think of linen when they think of Irish textiles, they also made a substantial amount of garments, including shirts, jeans and uniforms.

Sadly the Northern Irish textile industry has been even more greatly effected than the rest of the UK, with barely a hundred or so manufacturers left. Those that remain have done so because they have adapted, and because they have become specialists in high-end manufacturing. None of the factories that I visited served the price-pressured high street anymore. Instead they work with luxury clients all over the world.

First up was a stop at Francis Dinsmore at Templemoyle Mills. Originally established over two centuries ago by Augustian monks who were experts in dyeing, Dinsmore are specialists in cotton dyeing and finishing. I met with the company’s owner Barry Corrigan, who gave me a tour of the mill.

Run by the Dinsmore family from 1791 to 2007, the business was bought Barry, then managing director, in 2007, because he didn’t want to see the factory knocked down and turned into flats. “You can only benefit by building property on the site once, whereas with textiles you can go on and on,” he tells me.

Barry talked with great passion about the many new business opportunities that he has made happen since he took over and it is clear why he has managed to more than double turnover in the last decade. Adding synthetic dyeing and cotton waxing, to the cotton dyeing and finishing that the Dinsmore were already doing, has greatly increased the variety of customers and industries that the business serves.

Supplying a broad variety of different customer bases is what has helped Dinsmore to survive where other textile companies in Northern Ireland have fallen by the wayside. Their customer base is as diverse as furnishing wholesalers, apparel companies, accessories manufacturers, the automotive trade and the book-binding industry. If you have a copy of the Koran it may be covered with fabric finished at the Francis Dinsmore mill.

Most recently the firm has set up an area to apply a waxed finish to cotton cloth under the brand name Templemoyle Mills. Named after the building in which Dinsmore are based, the fabric is used for outerwear, luggage, and accessories. If you are looking for waxed cotton fabric do check out Templemoyle Mills. They have loads of different weights, colours and finishes of the fabric in stock and they can supply it in quantities as small as 50 metres.

The fabric dyeing trade can be one of the most polluting parts of the textile industry. You only have to look at the pictures of Chinese rivers in rainbow shades – a bi-product of dye houses flushing out into rivers. Barry tells me that Dinsmore have stopped using many chemicals now that would have been used in the past, and many chemicals that are still approved for use, they don’t even touch.

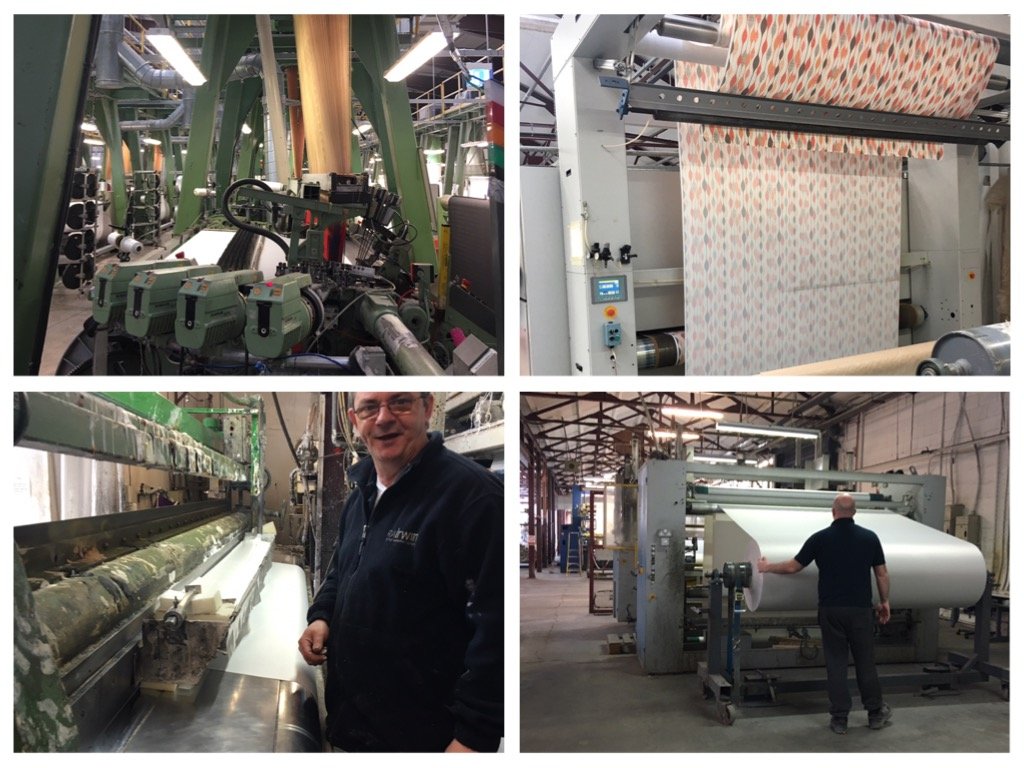

My next stop was RA Irwin. Originally founded in 1951 as a handkerchief manufacturers, they are now a fully vertical weaver, finisher and printer of fabrics for blinds and bedding.

Still a family company, I was shown around by Richard Irwin, the grandson of the founder. It is a wonder that Irwin is still in business, having survived both a fire in 1985 and a flood in 2008. But the Irwin’s are obviously a resilient bunch. And also very adaptable too.

When hankies went out of fashion, instead of packing it in, the business quickly switched to being a warp knitter. Then in the late ’90s they spotted an opportunity in weaving for the furnishing industry. With 34 looms and weaving 100,000 metres of cloth a month, they are probably one of the biggest weavers in the UK.

The fabric that they weave is made into all different types of blinds – including 1,000 metres a week of blackout blinds produced to meet a growing demand from parents for totally dark rooms for sleeping babies!

Irwin were also one of the first UK textile manufacturers to invest in digital printing technology – buying their first fabric printer in 2008 so that they could produce printed blinds to add to their collection.

Supplying through household names such as Hillary’s Blinds, Silent Night, Bensons and Dreams, chances are, you have had fabric woven and finished by RA Irwin in your property or workplace at some point in time.

After RA Irwin we headed down to Banbridge to the last remaining linen weaver in Northern Ireland – Thomas Ferguson Irish Linen, where I was greeted by one of their directors – Judith Neilly.

There used to be 38 weavers in Banbridge alone. Now Fergusons are the last of their kind, and have remained in business due to their diverse range of customers. They supply everyone from London Fashion Week designers, film and TV and the furnishing industry under their John England brand of linen fabrics. As well as the Scouts and Girl Guides with badges which they embroider onsite under their Franklins brand. Visit any gift shop in Northern Ireland you will find Irish linen products made by Thomas Ferguson.

If you have ever watched Game of Thrones you would have seen plenty of fabrics woven at the Ferguson mill. Judith works very closely with the TV show’s costume department to create fabrics for the costumes for the show. She explains that linen has the perfect properties for TV – having the ability to look very aged and worn when it is creased, and the ability to look brand new again once it is washed and ironed.

Their weaving shed is vast, housing dozens of jacquard looms noisily hammering away producing the finest Irish linen cloth. They also have a sewing room where the cut and finish all of the linen tableware that they sell all over the world.

The range of cloth produced at the Ferguson mill is extremely diverse – from open, net-style weaves used in the latest Star Wars movies, to a lustrous indigo-dyed denim factory made by combining linen in the warp and cotton in the weft of the fabric.

To get an idea of the vast array of fabrics in John England range take a look at their website, or find them exhibiting at our Meet the Manufacturer trade show in May.

My final visit of the day finished on a high, as I had the opportunity to step inside Ulster Carpets in Portadown. I’ve never been in a carpet weaving mill before, so this was a real treat. Especially given that Ulster Carpets are not only the largest carpet manufacturers in the UK, but one of the top producers in the world.

I was taken inside the mill by David Acheson, the mill’s Head of Strategic Operations. Unfortunately, due to the unique patented technology that Ulster Carpets have introduced to their looms to make them more efficient, I was unable to take any photos. So you’ll just have to take my word for it that it was amazing!

The Ulster Carpets mill produces 40,000 metres of carpet per week, 70% of which goes outside of the UK. One of their biggest markets is casinos, so you can image the crazily patterned flooring that some of the looms were churning out.

The mill gets through 1.8 million kilos of wool every year, with 80% of the fibre being British wool. They have recently built a new dyehouse too, which uses some of the most up-to-date technology to dye the yarn, including robotised machinery. No one could ever say that the textile manufacturers of Northern Ireland were lacking in innovation!

On day two of my tour I had the pleasure of visiting Bridgedale socks, an extremely modern sock factory in Newtownands, not far from Bangor. They’ve been knitting socks here since 1950, and are specialists in socks for the outdoor market.

I am astounded by the complexity that can go into producing a sock. For a start, several different yarns, such as Merino, polypropylene, nylon and Lycra, are twisted together so that each can be used to create a part of the sock with distinct properties. For instance, some areas may require cushioning, whilst others have a more open construction for ventilation. Plus there’s all the different colours that go into the sock’s design too.

Once the yarn is prepared it moves over to the circular knitting machines, of which there are 52 at Bridgedale. Each one spits out a fully finished sock in around 3 minutes and the factory produces 1.2 million socks a year.

After the knitting process each sock is applied to a strange looking upside-down flat leg, which takes it through a steaming chamber in order that it is ready to go into its packaging. After careful inspection to ensure that it meets the high quality expected of a Bridgedale sock it is then packaged and ready to be shipped.

Over 45 percent of Bridgedale’s socks end up on feet outside the UK, in 42 countries across the world. Each pair is guaranteed for three years, “but often last much, much longer” says the firm’s Director of Operations Jim Campbell.

Last stop on my whirlwind tour of the textile manufacturers of Northern Ireland was Ulster Weavers. Despite the name, the 127 year old company has not woven cloth for many years. They moved into the home textile market in the 1960’s, specialising at first in Irish linen tea towels. Over the years that have extended their product ranges to include all types of kitchen items.

Last stop on my whirlwind tour of the textile manufacturers of Northern Ireland was Ulster Weavers. Despite the name, the 127 year old company has not woven cloth for many years. They moved into the home textile market in the 1960’s, specialising at first in Irish linen tea towels. Over the years that have extended their product ranges to include all types of kitchen items.

Whilst Ulster Weavers no longer produce cloth in the UK, they do have a screen-printing facility in Northern Ireland and produce finished home textile products for both their own range as well as bespoke work for other clients.

So, that’s a brief summary of my textiles tour of Northern Ireland. I would love to go back, as there is so much more than could be seen in two days. There are still several shirt manufacturers there, as well as some wool weavers in Mourne that I would have liked to have got to.

I was also due to visit Wm Clark on this trip, the oldest textile business still in operation in Northern Ireland. But sadly the mill had a serious fire the day before I was due to arrive, and understandably they weren’t up for a visit. I do hope that they get back into operation soon, it would be devastating to see the business close down. But if all of the manufacturers that I met on my visit were anything to go by, it would take more than a fire to keep an Irish textile business to get them down!