Coronation Festival’s ‘Best of British’ reveals that not all Royal Warrant holders make their products in the UK

Yesterday I had the good fortune to be able to attend the Coronation Festival – an event held in the grounds of Buckingham Palace to celebrate 60 years since Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. Held over 4 days and hosted by the Royal Warrant Holders Assosciation, the event brought together over 200 companies who are entitled to display the Royal Arms on their products and packaging because they supply goods or services to the Royal Household. The show featured a diverse range of businesses, from British car makers Bentley, cloth weavers Hainsworth and handbag brand Launer to pharmacists to the Queen, John Bell & Croyden and Rokill, who provide pest control services to the Palace.

The bestowing of a Royal Warrant dates back to 1155 when Royal Charters were granted to the trade guilds, later known as Livery Companies. The earliest recorded Royal Charter was granted by Henry II to the Weavers’ Company and in 1394 Dick Whittington helped to obtain a Royal Charter for his own company, the Mercers, who traded in luxury fabrics. By the 15th Century it had become known as a Royal Warrant of Appointment and one of the first recipients of this was William Caxton, England’s first printer, who was appointed King’s printer in 1476.

During her current reign Queen Elizabeth and her family have granted more than 1,000 Royal Warrants, and currently around 800 companies are by appointment to her Majesty, with over 200 of these taking part in this weekend’s Coronation Festival celebrations.

Over the years the marque of the Royal Warrant has become known to represent British craftsmanship at its best and this was certainly in evidence in the quality of goods displayed by the Royal Warrant holders at this one-off event. However, whilst the vast majority of products on display were crafted in the British Isles, there were still a few who were displaying goods which I know to be made in the Far East. Even the catwalk show which took place at the event under the title Best of British featured products that were not manufactured here.

So is this a problem? Should Royal Warrant holders have been allowed to bring foreign-made goods to an event that is supposed to be presenting the Best of British? “It’s not right”, said Cass Stainton, an employee of Dege & Skinner, whose bespoke suits are all hand-crafted on Saville Row. “We’ve been invited here at Her Majesty’s pleasure and should be presenting products that are made in Britain”.

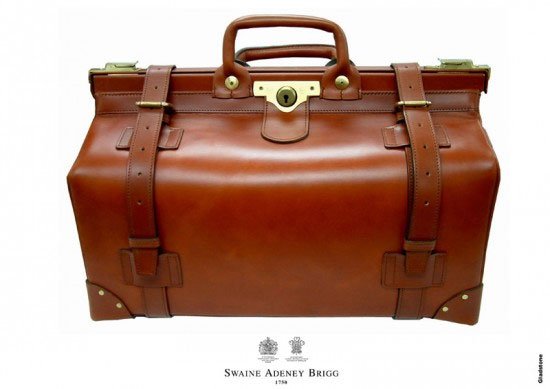

Roger Gawn, chairman of Swaine Adeney Brigg, who makes all of his products in the UK, was equally unimpressed. “It’s wrong that they should be allowed to do this…I think that a British brand should mean that it is made in Britain, and I don’t think it’s right that some here are not”.

Other exhibitors that I spoke to were more philosophical about the fact that some Royal Warrant holders do not manufacture their goods in Britain anymore. Lisa Wood, MD of Corgi, who hand make all of the socks that they sell to Prince Charles at their factory in Wales, had this to say about the importers, “some goods just aren’t made here anymore because of changes in fashion or whatever, so what can they do?”.

What do you think? Should a Royal Warrant only be bestowed on companies that manufacture their products in the UK? What about those that already hold a Royal Warrant but move the production of their goods offshore whilst in possession of the honour? Should the Warrant then be taken away? These are certainly the views of Ian Buckley, who commented on this blog a few months ago: “Seems to me the Royal Warrant is applied regardless of where products are made. They even give it to British companies who move production overseas and put people out of work, (e.g.. Cadbury).”

There are already strict rules in place to ensure that businesses are entitled to keep their Royal Warrant – each holder must re-apply every 4 years and is required to demonstrate, among other things, that they have a sustainable environmental policy and action plan in place. If their goods or services are no longer deemed up to the required standard then their Royal warrant is taken away. Should this re-application also ask them to provide evidence that wherever possible they are continuing to support British industry by manufacturing their goods in the UK?

What do you think?